Jill Prior leading a revolutionary legal centre for women

Jill Prior is the inaugural Principal Legal Officer of the Law and Advocacy Centre for Women, a unique legal practice designed for women who are in, or at risk of entering, the criminal justice system. Alongside legal representation, the Centre provides services such as counselling and housing support, offering a holistic approach that helps to address many of the reasons women come in contact with the justice system such as poverty, homelessness, and mental health. I’m so pleased to speak with Jill about the Centre and the difference it’s making to the lives of so many vulnerable women.

Interview by Maria O’Dwyer Photography Mia Mala McDonald

Maria O’Dwyer: You are the co-founder and Principal Legal Officer at the Law and Advocacy Centre for Women – a revolutionary legal centre in Melbourne. What led you to found the Centre?

Jill Prior: In 2014 I made the very difficult decision to leave my role as the Principal Legal Officer at the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service – an organisation I had been with for over 10 years.

I knew that I would need to work in a way that inspired me as much as that role. At that time there was an obvious gap in legal services for women charged with criminal offences and I was incredibly fortunate that my co-founder Elena Pappas agreed to come on this journey with me. It was a leap of faith that we were on the right path and that there was a need for this kind of a service.

Why create a legal service specifically for women?

Women are rapidly increasing in their contacts with the criminal justice system. Historically, the courts see huge numbers of men but the numbers of women were becoming more and more significant. We saw that a response to those women would produce different outcomes as their pathways into the criminal justice system were unique to that cohort. That is, family violence, histories of victimisation, homelessness, mental health issues, poverty were presenting markers for most of these women. That calls for a different response.

The Centre has been described as having a multidisciplinary approach with a therapeutic focus. What does this mean?

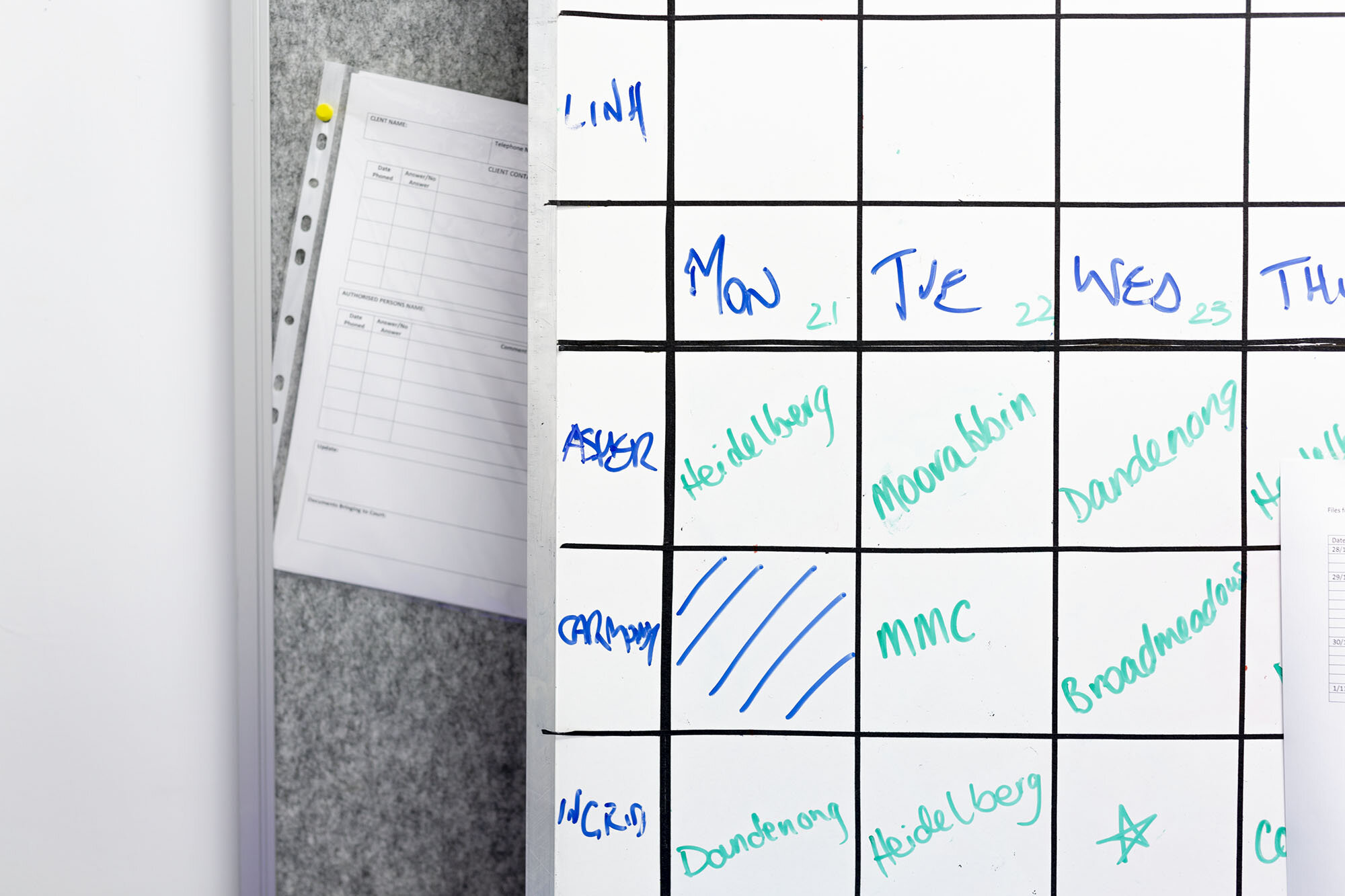

We have been fortunate to be co-located now for most of our history. Initially, we were supported with a space at the Djirra (Aboriginal Family Violence and prevention legal service) and then with the Centre for Innovative Justice at RMIT. This colocation has helped us to establish ourselves and to grow, but also creates relationships that allow student placements with our organisation – in social work and law – and to look at feeding research with the Centre for Innovative Justice. In terms of the therapeutic focus, when we looked at a new practice we knew that there were almost always underlying determinative factors that impacted on women that saw them make contact with the justice system. To have social workers in-house allows us to work with the women to address issues around housing, disability, drug and alcohol and mental health whilst their legal matter progresses. Our case managers are guided by those women in terms of their needs whilst the lawyers work on their legal case.

The legal profession is often considered very conservative. What did it take to set up a new legal centre with such a radical approach?

The thing about our model is that it really isn’t that renegade or particularly controversial. If we can impact on our client’s lives positively when things are not going well then we are creating possibilities that have long-term impact. When only a legal response occurs to issues that are deeply impacted by social and economic factors (and a plethora of other complexities) then we are really losing an opportunity to effect change and divert women from the courts. The Courts themselves are generally receptive to this type of lawyering. In fact, if the community were educated on the benefits of such an approach there would be, I am sure, wholesale support for such a response.

As someone who works with women who are experiencing stress and trauma on a daily basis, how do you avoid taking this home with you?

I am blessed to have been raised in a kind and loving family with unwavering belief in me. I have the privilege of my position in the community and I feel incredibly lucky to be able to work with people who have powerful stories of resilience and strength in the face of adversity and challenges that would make you weep. I am greatly strengthened by my learnings from clients over the years and it is incumbent upon us, as advocates, to be angry about how some people are treated in our society. We must push for a voice for those without one. It is absolutely true that our clients tell us stories of significant trauma and this, of course, impacts on us. But there is a strength in the advocacy in response to those stories we hear – the fire in the belly is stoked.

You come from a family of social workers – how much did they impact on your work in the social justice sector?

My immediate family, and extended family work tirelessly in the community and represent the interests of those in the community who are marginalised. We were raised, probably, with the great hope of our parents that we would live in the world with this kind of work. I guess it was bred into us from a young age, we always had an open house and people who were struggling in various ways were frequently around. This was normal for us, rather than a hindrance or burden or something to be feared. Our parents have lived their lives guided by these principles and my father, in particular, was absolutely unafraid of speaking in the spaces of great discomfort on behalf of those without voice.

We’re in an era, ‘post me-too’, where we see women championing other women and calling out sexist behaviour – and with the help of the internet there seems to be more awareness of the power of women than ever before. Yet in Victoria, women are more likely than men to fall into poverty. What do you think it’s going to take for real equality to happen?

It seems to me that women have a great strength in community and a resilience that persists despite pain, trauma and victimisation. I see women with nothing regularly holding up others who need it. In terms of calling out sexist/misogynist and violent behaviour – this ought to sit with everyone so there is a societal shift and a level of contempt for those pervasive behaviours. We must remember, though, that movements such as #metoo and mediums such as the internet are very much vehicles of relative privilege. Our clients have nowhere to sleep, their children have been removed, they are poor and often at risk of violence. But not one of the almost 1000 women we have seen has spoken to me about #metoo.

What do you hope the future looks like for women? What needs to change?

Women will lead the changes that are needed. And those women will be guided by their own communities – there is amazing strength in Victoria’s Aboriginal communities and the women seem to be leading those voices. We need to listen to what women and communities are saying is needed. Listening and respect.

Although, in our family the Prior theme song was Helen Reddy’s “I am Woman”. Many car trips enjoyed loud renditions of that song – perhaps that will help!